Archive

The New School Accountability Regime in England: Fairness, Incentives and Aggregation

Author: Simon Burgess

The New School Accountability Regime in England: Fairness, Incentives and Aggregation

The long-standing accountability system in England is in the throes of a major reform, with the complete strategy to be announced in the next few weeks. We already know the broad shape of this from the government’s response to the Spring 2013 consultation, and some work commissioned from us by the Department for Education, just published and discussed below. The proposals for dealing with pupil progress are an improvement on current practice and, within the parameters set by government, are satisfactory. But the way that individual pupil progress is aggregated to a school progress measure is more problematic. This blog does not often consider the merits of linear versus nonlinear aggregation, but here goes …

Schools in England now have a good deal of operational freedom in exactly how they go about educating the students in their care. The quid pro quo for this autonomy is a strong system of accountability: if there is not going to be tight control over day to day practice, then there needs to be scrutiny of the outcome. So schools are held to account in terms of the results that they help their students achieve.

The two central components are new measures of pupils’ attainment and progress. These data inform both market-based and government-initiated accountability mechanisms. The former is driven by parental choices about which schools to apply to. The latter is primarily focussed around the lower end of the performance spectrum and embodied in the floor targets – schools falling below these triggers some form of intervention.

Dave Thomson at FFT and I were asked by the Department for Education (DfE) to help develop the progress measure and the accompanying floor target, and our report is now published. Two requirements were set for the measure, along with an encouragement to explore a variety of statistical techniques to find the best fit. It turns out that the simplest method of all is barely any worse in prediction than much more sophisticated ones (see the Technical Annex) so that is what we proposed. The focus in this post is on the requirements and on the implications for setting the floor.

The primary requirement from the DfE for the national pupil progress line was that it be fair to all pupils. ‘Fair’ in the sense that each pupil, whatever their prior attainment, should have the same statistical chance of beating the average. This is obviously a good thing and indeed might sound like a fairly minimal characteristic, but it is not one satisfied by the current ‘expected progress’ measure. We achieved this: each pupil on whatever level of prior attainment an expected progress measure equal to the national average. And so, by definition, each pupil has an expected deviation from that of zero.

The second requirement was that the expected progress measure be based only on prior attainment, meaning that there is no differentiation by gender for example, or special needs or poverty status. This is not because the DfE believe that these do not affect a pupil’s progress, it was explicitly agreed that they are important. Rather, the aim was for a simple and clear progress measure – starting from a KS2 mark of X you should expect to score Y GCSE points – and there is certainly a case to be made that this expectation should be the same for all, and there should not be lower expectations for certain groups of pupils. (Partly this is a failure of language: an expectation is both a mathematical construct and almost an aspiration, a belief that someone should achieve something).

So while the proposed progress measure is ‘fair’ within the terms set, and is fair in that it sets the same aspirational target for everyone, it is not fair in that some groups will typically score on average below the expected level (boys, say) and others will typically score above (girls). This is discussed in the report and is very nicely illustrated in the accompanying FFT blog. There are plausible arguments on both sides here, and the case against going back to complex and unstable regression approaches to value added is strong. This unfairness carries over to schools, because schools with very different intakes of these groups will have different chances of reaching expected progress. (Another very important point emphasised in the report and in the FFT blog is that the number of exam entries matters a great deal for pupil performance).

Now we come to the question of how to aggregate up from an individual pupil’s progress to a measure for the school. In many ways, this is the crucial part. It is on schools not individual pupils that the scrutiny and possible interventions will impact. Here the current proposal is more problematic.

Each pupil in the school has an individual expected GCSE score and so an individual difference between that and her actual achievement. This is to be expressed in grades: “Jo Smith scored 3 grades above the expected level”. These are then simply averaged to the school level: “Sunny Vale School was 1.45 grades below the expected level”. Some slightly complicated statistical analysis then characterises this school level as either a significant cause for concern or just acceptable random variation.

It is very clear and straightforward, and that indeed is its chief merit: it is easily comprehensible by parents, Headteachers and Ministers.

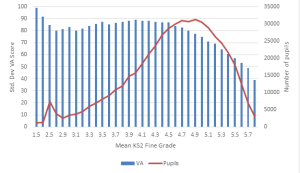

But it has two significant drawbacks, both of which can be remedied by aggregating the pupil scores to school level in a slightly different way. First, the variation in achieved scores around expected progress is much greater at low levels of attainment than at high attainment. This can be seen clearly in Figure 1, showing that the variance in progress by KS2 sharply and continuously declines across the range where the bulk of pupils are. Schools have pupils of differing ability, so the effect is less pronounced at school level, but still evident.

The implication of this is that if the trigger for significant deviation from expected performance is set as a fixed number of grades, then low-performing students are much more likely to cross that simply due to random variation than high-performing students are. By extension, schools with substantial intakes of low ability pupils are much more likely to fall below the floor simply through random variation than schools with high ability intakes are. So while our measure achieves what might be called ‘fairness in means’, the current proposed school measure does not achieve ‘fairness in variance’. The DfE’s plan is to deal with this by adjusting the school-level variance (based on its intake) and thereby what counts as a significant difference. This helps, but is likely to be much more opaque than the method we proposed and is likely to be lost in public pronouncements relative to the noise about the school’s simple number of grades below expected.

Fig 1: Standard deviation in Value added scores and number of pupils by mean KS2 fine grade (for details – see the report)

The second problem with the proposal is inherent in simple averaging. Suppose a school is hovering close to the floor target, with a number of pupils projected to be significantly below their progress target. The school is considering action and how to deploy extra resources to lift it above the floor. The key point is this: it needs to boost the average, so raising the performance of any pupil will help. Acting sensibly, it will target the resources to the pupils whose grades it believes are easiest to raise. These may well be the high performers or the mid performers – there is nothing to say it will be the pupils whose performance is the source of the problem, and good reason to think it will not be.

While it is quite appropriate for an overall accountability metric to focus on the average, a floor target ought to be about the low-performing students. The linear aggregation allows a school to ‘mask’ under-performing students with high performing students. Furthermore, the incentive for the school may well be to ignore the low performers and to focus on raising the grades of the others, increasing the polarisation of attainment within the school.

The proposal we made in the report solves both of these problems, the non-constant variance and the potential perverse incentive inherent in the averaging.

We combine the individual pupil progress measures to form a school measure in a slightly different way. When we compare the pupil’s achievement in grades relative to their expected performance, we normalise that difference by the degree of variation specific to that KS2 score. This automatically removes the problem of the different degree of natural variation around low and high performers. We then highlight each pupil as causing concern if s/he falls significantly below the expected level, and now each pupil truly has the same statistical chance of doing this. The school measure is now simply the fraction of its pupils ‘causing concern’. Obviously simply through random chance, some pupils in each school will be in this category, so the floor target for each school will be some positive percentage, perhaps 50%. We set out further details and evaluate various parameter values in the report.

The disadvantage of this approach for the DfE is that the result cannot be expressed in terms of grades, and it is slightly more complicated (again, discussed in the report). This is true, but it cannot be beyond the wit of some eloquent graduate in government to find a way of describing this that would resonate with parents and Headteachers.

At the moment, the difference between the two approaches in terms of which schools are highlighted is small, as we make clear in the report. Small, but largely one way: fewer schools with low ability intakes are highlighted under our proposal.

But there are two reasons to be cautious. First, this may not always be true. And second, the perverse incentives – raising inequality – associated with simple averaging may turn out to be important.

Profits in schools – response

Author: Simon Burgess

Profits in schools – response

There were some interesting comments on the recent post I wrote on profit-making schools. This post offers a brief reply to those points.

First, one comment was that allowing profit-making is a solution to the lack of capital for schools:

“advocates see profit-making as a way to tap the private finance that might allow supply-side liberalisation, which would in turn allow choice to operate more effectively than it does at present. Theoretically, of course, this boost to capacity could be done with public finance. But it’s questionable whether the necessary level of spare capacity would be politically sustainable given all the other calls on public spending (especially now). So private finance is (arguably) one solution to that problem.”

It may be a solution to that problem, but it is not a necessary solution, there are other ways. The PFI programme has been funding capital spending on schools for over a decade now. Nor is it just a thing of the past: in 2011 Michael Gove announced capital expenditure through PFI of around £2bn to rebuild 300 schools. The latest estimates are that PFI expenditure on education will top £260m in 2012-13, and the whole programme has generated over £7bn for school building. The PFI obviously utilises the profit motive in the capital market to get funds into school building without needing profits in the schools themselves.

Second is the question of just how profits can be made. Given fixed revenue per student, it is not possible to directly make a greater rate of return by raising quality (the indirect route is discussed below). Profits can be made by reducing costs. This may be possible without reducing quality, or not. That possibility is that other agents can come in, re-arrange the budget, reduce costs and maintain quality by raising quality per pound spent. The comment was:

“You also argue that ‘outsiders’ are unlikely to know best how best to deploy their budgets. This seems like an odd argument. The market’s virtue is supposed to be innovation and the ability to scale good practice quickly through incentives to mimic the best. If you don’t think that works then I can’t see why you’d be interested in the practical aspects of for-profit schools, since there wouldn’t even be any benefits in principle.”

It is certainly true that schools are unlikely to be making completely optimal decisions. Our own work shows a huge degree of heterogeneity in schools’ financial decisions which is very unlikely all to be optimal. So they certainly have scope for learning. And schools may be able to learn from each other: a lot of people interpret the success of London schools as down to ‘London Challenge’ – and a lot of people interpret the success of that to collaboration, to learning from other schools. In fact, we are in the design stage of a large-scale RCT to test this out. But the key point is that with the current system for school revenue, allowing profit-making provides incentives to reduce costs but no direct incentive to raise quality. So again profits might be a way of encouraging collaboration, but there are other, easier, ways of doing the same thing.

The indirect channel for profit making to affect quality is a dynamic one. The third comment is:

“Presumably if you designed the admission and information systems properly then schools in which children make more progress will expand (either on site, or on another site) due to increased demand This could either come from parents choosing higher performing schools or commissioners awarding contracts/charters to higher performing schools. Then, assuming the school makes a fixed profit on each student they ‘process’, they will increase their profit through increased market share. Student progress up > Market share up > Profit up.”

The key here is the word “presumably”. Yes – this is the standard dynamic market process. If this worked in schools, then this would make choice and competition more effective in raising quality. But it does not appear to work well, as we described here. Understanding the best way to reform the revenue stream for schools to encourage expansion is the important part; profit-making may eventually be part of an incentive mechanism, but is currently tangential to the main problem.

I’m an economist, I believe that incentives matter hugely. Indeed, many of the things that I write or say to the Department for Education involve the phrase “you need to make it matter more”. But that is about individual incentives: perhaps making the pay of Headteachers contingent on school outcomes, perhaps introducing some form of performance incentive for teachers. These people can raise quality, and can be rewarded for doing so.

Within the present rules of the game, schools cannot be rewarded for raising quality, because the revenue they would receive is independent of quality. Clearly, profit-making schools can introduce individual performance incentives; but so can – and have – non-profit making schools. Again profit-making is a side issue. It’s the wrong battle to fight.

Teacher performance pay without performance pay schemes

Author: Simon Burgess

Teacher performance pay without performance pay schemes

Amid the macroeconomic gloom, the Autumn Statement contained a line about teachers’ pay. The School Teachers’ Review Body recommends “much greater freedom for individual schools to set pay in line with performance”. Consultations and proposals are expected in the near future.

But simply giving schools the freedom to do this may be a rather forlorn hope of anything much happening. It is not clear that there is a substantial demand from schools for performance-related pay (PRP) schemes that has only been thwarted by bureaucratic restrictions. It is hard to see high-powered, tough-minded PRP schemes being introduced by more than a handful of schools, not least because we have not seen large scale deviations from national pay bargaining in academies in England despite their new freedoms to do so.

If that path seems unpromising, there are other ways of facilitating a greater reflection of performance in pay, discussed shortly. But first – is PRP for teachers a good idea in the first place? Does it raise pupil attainment? What are the ‘side effects’?

This is a question that economists have produced a good deal of research on. And to summarise a lot of diverse work briefly, the international evidence is mixed. Those on both sides of the argument can point to high quality studies by leading researchers that find substantial positive effects, or no effects. In both cases, interestingly, there appeared to be little evidence of gaming or other unwanted effects of the incentives.

There is little evidence specifically for England. Our own research found a substantial positive effect of the introduction of a PRP scheme, but given the varied results found elsewhere it would seem unwise to place too much weight on this one study. The underlying performance pay scheme was poorly designed but nevertheless had a positive effect on the progress of pupils taught by eligible teachers relative to ineligible ones.

And design is key. There are many reasons why a simple high-powered incentive pay scheme might be detrimental to pupil progress, which we have discussed here and here. These include the fact that teachers have multiple tasks to do, the problems of measuring the outcomes of some of those tasks, the complex mixture of team and individual contributions, and the potential impacts on implicit motivation. The overall message is that incentives work, but schemes have to be very carefully designed to achieve what the schemes’ proponents truly intend.

There is another way to facilitate a closer link between pay and performance that does not require any school to introduce a performance pay scheme.

Published performance information in a labour market can change the way that the market rewards that performance. The critical features are first that the organisation’s own output depends in an important way on this performance characteristic of an individual; second that the organisation has some discretion in the pay offers it can make to new hires; and thirdly that the performance information is public – is available and verifiable outside the current employer. In this case, the pay structure of the market will reflect the performance rankings: high-performing individuals will be paid more.

In teaching, the first two of these three conditions are met: teacher quality matters hugely for schools, and schools have some discretion over pay. Now, suppose we had a simple, useful and universal measure of each teacher’s performance in raising the attainment of her pupils (obviously we don’t at the moment; I come back to this below), and that this was published nationally, primarily for the attention of Headteachers. The idea is that Headteachers trying to improve the attainment of their pupils would be on the look-out for high performing teachers when they had a vacancy to fill. Armed with this performance information, they might try offering a higher wage (or something else – it doesn’t have to be money) to tempt them to join their own school. Equally, the teacher’s current school may respond by raising the offer there. Over time, this process will tend to raise the relative pay of high-performing teachers relative to low-performing ones, whom no-one is trying to bid for.

This idea should not be a strange one. A number of professions have open measures of performance. Just today it is reported that performance measures for more surgeons will be made public in the summer of 2013; this is already true for heart surgeons.

It is well-known that PRP does two things: it motivates and it attracts. The outcome for pay described here will tend to make teaching more attractive to people who are excellent teachers and less attractive to those who aren’t.

There are a number of problems with this idea, though perhaps less than might appear at first glance. First, it could be argued that a performance measure derived from teaching in one school is not relevant to teaching in another school. Obviously each child and each school is unique, but it seems very unlikely that there is no commonality of context between one school and the next. Observation suggests this: teachers moving from one school to another are not counted as having zero experience, and Headteachers are often appointed from outside a school.

Second, there might be a fear that the teacher labour market would become chaotic, with everyone churning around from school to school in search of a quick gain. We have to recognise that there is substantial turnover of teachers now < http://www.bristol.ac.uk/cmpo/publications/papers/2012/wp294.pdf >. But the main point is that it does not require much actual movement to make the market work. Schools can make counter offers to try to retain their star teachers and the end result is the same – higher salaries for high-performing teachers.

Third, any measure would be noisy, partial and imperfect. Of course, all such measures are. Whether a measure is perfect is not really the question, the question is how noisy and imperfect is it, and whether it contains enough information to be useful. One advantage in this case is that the consumers of these performance indicators are the people best able to judge their usefulness and their shortcomings: Headteachers. If such metrics are not useful, Headteachers will simply ignore them; there would be no compulsion to use them. Even in labour markets with some of the most detailed and finely measured performance indicators (for example, football or baseball) there are many moves between employers that do not work out. It is worth re-emphasising that these performance measures are bound to be imperfect and incomplete, but broad measures of performance may nevertheless be very useful.

There are useful parallels to be drawn from another profession: academics. For academics, the combination of very detailed and public performance information and a context where research performance matters a great deal to universities seems to have had a substantial effect on academics’ pay.

The Research Assessment Exercise (RAE) and more recently the Research Excellence Framework (REF) have made a strong research performance very important to a university’s standing and its income. But the critical factor for academics is that an individual’s research performance is public knowledge, through very detailed recording of the impact of their research papers. Departments and universities aiming to improve their ranking seek out star researchers and attempt to bid them away with higher salaries (plus other things such as research facilities). These offers may well be matched by their current employer, but the end result is that salaries now seem to be much more closely correlated with research productivity than before the RAE/REF (I say “seem” as there does not appear to be any evidence on this, so this is casual empiricism). This is a lot of what drives many young researchers to put in very long work hours: having a paper published in a top scientific journal early in a career has a substantial lifetime payoff even in a world with few or low-powered incentive schemes. If you check out academics’ websites you will invariably see their academic output prominently displayed.

Again, an important feature is that these indices of research output are largely consumed by other academics who are aware of their strengths and weaknesses. So although they are far from perfect, they are used by precisely the people best placed to calibrate their usefulness appropriately.

If we are to go down a path of tying teacher pay more closely to performance, and yet respect the rights of increasingly autonomous schools to determine their own pay systems, then this might be an option to consider. The challenge is to devise a measure that is simple, useful and universal. It would measure the progress made by the pupils that teachers taught, it would have to deal with normal variations in performance by averaging over a number of classes and a few years, and be on a common metric. This is not straightforward, but if it gave rise to a robust broad measure of performance it could form a part of performance pay for teachers, and performance management more broadly. It could also have substantial effects on the pay of high-performing teachers.

Charitable Giving – How hard can it be?

Jeremy Clarkson, of Top Gear fame (among other things), made use of his column in this Sunday’s News Review[1] (in the Sunday Times, paywalled), to bemoan the death of philanthropy, and to propose a surprisingly economist-friendly explanation; the arrival of substitutes.

As Mr Clarkson says, “it’s because in the days of (William) Morris, and my great-granddad there wasn’t much you could actually buy”. Certainly it is true that since the 1930s the sheer number of status symbols required to maintain the kind of upper-middle-class lifestyle expected of a Times columnist has increased dramatically, and it is also true that charitable giving is, for many parts of society, on the decline[2]. That people, when given the choice between buying mosquito nets for others half way around the world or a new iPad for themselves, choose the iPad, seems intuitively simple. It is also on sound footing economically; if a preferred substitute comes along, from which you extract greater utility, substituting from one into another is only natural, and as the relative price of the substitute declines (as is typical for technology), we might expect the level of this substitution to increase.

Governments of all stripes appear to have agreed with this basic assessment, with the last Labour government reducing the ‘price’ of giving by making Gift Aid, a tax-efficient means of giving, available on donations of all sizes (previously it was available only on donations of £250 of more), and the current, coalition government, aiming to increase the ‘return’ on giving through rises in the Gift Aid Benefit Limit to “enable charities to give ‘thank you’ gifts”[3].

If all this seems sensible, what can we say about the conclusion to the article, that for Philanthropists, “their investment is going to make them a damn sight happier than the man who spent his cash…” on something more frivolous. Traditional economic theory suggests that this should not be the case. Following the Weak Axiom of Revealed Preference (WARP), if an individual chooses to buy a grande skimmed-milk extra shot mocha rather than mosquito nets, we can conclude that he prefers, given his income constraints, coffee to mosquito nets. Simplistically, this situation appears to be Pareto optimal – it is impossible to make one party (those at risk of mosquito-borne-disease) better off, without worsening the lot of another (our coffee drinker). Although it is possible to make a moral argument for redistribution from coffee to mosquito nets to improve social welfare, we might expect Clarkson’s pleading with us to give more to charity to fall upon deaf ears.

Some insight into why a narrow view of economics might seem to be wrong, and the Sunday Times’ most controversial columnist might be right, can be found in Behavioural Economics. A large quantity of research, summarized by Dellavigna (2009)[4] and Bernheim & Rangel (1995)[5], suggests that individuals may make decisions which are not only socially undesirable, but personally undesirable as well.

While changes in the relative price or value of giving may increase individuals giving, it is, of course, costly to do so, and will be less effective than governments might hope if, as the literature suggests, would-be donors are inattentive to the benefits of giving, or to the changes in policy.

In the coffee vs nets example, we can see another reason for the government to explore in depth the lessons of behavioural economics when planning the “Big Society” – these lessons are already being learned, and to great effect, by the firms with which charities are competing for funds. The placement of biscotti, mints and caramel waffles near the till in coffee shops, the offer made by baristas or their local equivalent (“would you like to go large on that?”), and defaulting to a mid-sized cups, are all Nudges; examples of behavioural economics put into practice.

It is clear that if the government is to achieve a ‘step change’ in the level of giving in the UK, and in so doing make both donors and recipients happier, charities will need the tools to compete with private firms and the willingness to use them – behavioural economics has the potential to offer those tools, and they are already being used to great effect by the competition.

[2] Smith et al (2011): “The State of Donation” Centre for giving and philanthropy.

[3] HM Treasury (2011) “Budget 2011” HM Treasury, HC836

[4] Dellavigna (2009): “Psychology and Economics: Evidence from the Field” Journal of Economic Literature Vol 47 No 2 pp315-372

[5] Bernheim & Rangel (1995): “Behavioural Public Economics: Welfare Policy Analysis with Non-Standard Decision Makers” NBER Working Paper 11518

3 million will face punitive tax rates under Universal Credit

Further details of the new Universal Credit were recently announced, with much fanfare. The plans integrate a number of different benefits and tax credits into one system which will make transitions in and out work administratively easier for claimants. The new system also makes taking mini-jobs (<16 hours) far more attractive, both to those out of work and to those currently working 16 to 20 hours in order to be eligible for the in-work tax credits introduced by Gordon Brown. When Ian Duncan Smith first discussed the need for reform he also highlighted the very high effective tax rates people face when earning more. We all pay income taxes on extra earnings but tax credits and the new Universal Credit are also withdrawn, leading to high effective tax rates. The details show what will happen to these effective tax rates under the new system and compares to what it calls the current system.

The current system will apply from April this year, which is important because the new government increased these effective tax rates in their first budget. The table below shows the figures announced today in the final two columns. It shows how the new regime will reduce the numbers of people with effective tax rates over 80%, but increase the numbers facing 70% to 80% tax rates. It will also increase the numbers facing 60-70% tax rates; this is people just on Universal Credit. Overall there is an increase of half a million people facing effective tax rates at 65% or over.

But this excludes the effects of the budget earlier this year and in the first two columns I report the numbers produced by HM Treasury at the time. They are not quite identical for the ‘current’ system for reasons that are not clear. But the point here is that this budget sharply increased the numbers facing tax rates between 70 and 80%, though to be fair this was mostly a move from 70% to 72 or 73%. But the point is that despite earlier statements from Ian Duncan Smith, the numbers facing punitive tax rates will have risen by 300,000 under this government and the normal tax rate for these people will have moved from 70 to 76%. As such the new regime encourages people to work a little bit, but reduces the incentive for people to work more.

| Marginal Effective Tax Rates | Financial year 2010/11 | Financial year 2011/12 | Current

|

Projected under Universal Credit (IFS) |

| 80%+ | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 0 |

| 70-80% | 0 | 1.4 | 1.7 | 2.0 |

| 60-70% | 1.6 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.9 |

| Under 60% | 1.3 | 0.9 |

Response to Education White Paper I: Teachers and teaching

Rebecca Allen and Simon Burgess

The focus of the new Education White Paper (WP) is advertised in the title: “The Importance of Teaching”. Teachers are rightly lauded as the most important single factor in creating a good education. The reforms relate principally to training new teachers, with additional discussion of the constraints and bureaucracy that teachers face. The White Paper calls for shifting the emphasis of teacher training from university-based to school-based training, the argument being that this is where the “craft” of teaching is better learnt, and that this will generate more effective teachers.

We believe that the WP presumes more robust evidence on this issue than actually exists. It is hard to legislate on the best way to train teachers when we are not really sure what makes a good teacher, or what effective teachers do. We need to be realistic in terms of what we know, and also in terms of the wider context around teacher development.

There are a number of prior questions that need more robust answers than they currently have to properly address this policy issue. For example: To what extent are good teachers born or made? What do effective teachers do? What motivates teachers? We discuss new teachers first and then existing teachers.

The two key issues around new teachers are recruitment and training. The research evidence suggests that the recruitment of teachers matters a great deal. This evidence can be used to design the ideal personnel policy, the ideal contract for teachers. The facts are that teachers are very different in effectiveness but that this is hard to spot pre-hire as it does not appear to be well correlated with characteristics such as degree class or subject; and that this level of effectiveness tends not to increase with experience after the first two or three years. The current teacher entry system involves making the sharpest selection before training (to be raised to a good university degree), giving training, but thereafter only mild selection: that is, most people pass their training, and then passing probation (achieving QTS) is relatively straightforward in most schools. The evidence suggests a better policy would be exactly the reverse: a much more open and inclusive approach to who can begin teacher training, coupled with a much tougher probationary policy.

It is hard to give strong advice about a model for teacher training, given only a sketchy idea of how effective teachers operate. But in practical terms, students on teacher training courses already spend about two thirds of their time in school rather than in the university lecture hall; the scope for major gains from further time in school does not seem large. Furthermore, a timely OFSTED report on initial teacher training found more outstanding university-based teacher training courses than outstanding school-based ones. The implications for schools of taking a larger role in teacher training also need some consideration, particularly given the squeeze in resources that is coming.

There are about 400,000 teachers in England, and the turnover is about 20,000 per year. So even if the average effectiveness of new teachers can be significantly improved, this will only have a marginal impact on overall effectiveness for at least a decade. Increasing the effectiveness of existing teachers offers much greater scope for rapid improvements in standards.

The counter-part to focussing initial training on schools is to emphasise and enhance training on the job, continuing professional development (CPD). The picture painted by the economics evidence suggests a model of informal, small-scale, within-school or even within-department groups would work well, with colleagues learning from the most effective teachers. Whilst CPD is discussed at some length in the WP, it has not been the focus of interest and discussion that it should be.

The broader question is why this has to be pushed towards teachers, why there isn’t much of a demand for it from most teachers. Raising the value of being an effective teacher might help fuel this demand. We know that teachers do raise their teaching effort given incentives, and it seems likely that they would also be keener to invest in their own capability to be effective. This incentivisation could be very simple and need not be personal financial gain. It could be simple pride and satisfaction from being top of a list of teachers in the staff room, or additional resources for a project chosen by the teacher, or it could be a pay bonus for the teacher.

The focus on teachers and teacher effectiveness is to be applauded. It is less clear that the right policies have been selected to enhance this.

Paying to fail?

Today, a very special education policy experiment was revealed.

In the past, policies have been introduced aiming to incentivise schools and teachers to raise educational attainment. These have been effective to a degree: our evidence shows that performance pay for teachers does raise educational attainment; competition among schools also has some impact, albeit much weaker.

This new policy incentivises students themselves. And in a break from past policies, this scheme directly incentivises students to fail their exams. It is reported that Blackburn College will pay £5000 to each student who fails her/his exams. This intriguing new policy will certainly add to the research evidence on how (not) to raise attainment.

This issue is taken seriously in the US with a number of landmark policy experiments raising attainment for some of the more deprived and low-attaining groups in the country. At Harvard, Roland Fryer reports on the results of a large scale experiment in which students were incentivised in different ways. In some schools students were paid on results, and in some schools they were paid for activities leading towards better results, such as attendance and completing homework. The results were mixed, but the latter class of experiments were effective and cost-effective. Similarly, C. Kirabo Jackson at Cornell has shown that the Advanced Placement Incentive Program in Texas produced some very exciting results from paying 12th grade students for test-passing scores. Such students are more likely to attend college, do better when they attend college and are less likely to drop out. Similar experiments have taken place in the Harlem Children’s Zone

These experiments give us an idea of the value of a policy to incentivise student achievement. As far as I know, Blackburn’s policy is the first chance we have had to study the value of a policy to incentivise student failure.

More seriously, the idea of a commitment device is standard: something that penalises the provider if something does not work out as planned. A long warranty on a car is one way of the manufacturer raising the cost to itself of the car failing. But in a case such as studying for exams, where student effort is so hard to observe, and where good or bad luck can play such a role, what economists call the “moral hazard” problem is very severe.

There are obvious alternatives – the College could pledge to give £5000 to a local charity for every student that fails the exam. That would still appropriately hurt the provider for failure on their part, without giving marginal students a very high temptation for failing at the last.

Cutting tax relief on pensions

The latest proposed spending cutbacks, announced today, are restrictions on the amount of money that can be paid tax-free into a personal pension each year – from £255,000 to £40,000 – and on the amount that can be built up in employer pensions.

While this will be unpopular with the pensions industry, this proposal has a lot to recommend it. There is a strong reason for the government to provide some incentives for people to save in a personal pension. Without tax advantages it is not an attractive form of saving because of its inflexibility – in the UK the money is locked away until retirement and then most of it has to be converted into an annuity (an annual income). This is exactly what the government wants people to do to prevent them from blowing their savings before or after retirement and falling back on the state – as apparently happens in countries such as Australia where annuitization is not compulsory. But without giving extra tax privileges, it is not clear that anyone would choose to save in this way. Following this argument, however, the “right” level of incentives will ensure that people build up a pot big enough to keep them off means-tested benefits (with a bit on top so they feel that the sacrifice has been worth it). There is no particularly strong economic reason to subsidize pensions above this level and allowing people to pay such huge sums tax free into a pension each year favours the better off.

Whether £40,000 is the right limit is harder to say. Means-tested benefits (pension credit) are currently worth £132.60 a week for a single person. You need a pension pot of more than £200,000 to get an annuity that will pay you this amount (for a woman aged 60 buying a single life annuity linked to inflation) – although this is an upper limit since most people will have some state pension that reduces the amount of means-tested benefit they receive. If people contribute to a pension during most of their working lives, the annual limit of £40,000 seems more than enough to reach this level of savings. There may be some, however, who were planning to concentrate their savings in a few good years who will be hard hit. More flexibility in being able to smooth contributions over years would help them.

However, it is less clear that the proposal will generate the type of savings that are currently being talked about – £4 billion a year in the cost of tax relief. These estimates typically assume that the money would otherwise be saved in a fully taxed form of saving – such as regular holdings of stocks and shares or a bank or building society account. This is clearly not the right counterfactual; wealthy savers will be seeking the advice of financial experts on the next best alternative to reduce the amount of tax that they have to pay.

The Browne Review and Incentives for Teaching in Universities

Incentives matter. Our research has shown repeatedly that this is true for the public sector as it is for the private sector: for teachers and schools, for doctors and hospitals and for civil servants. It is very likely also to be true for universities and those of us who work in them.

For the past couple of decades, universities have been very strongly incentivised to improve their research profiles. The evolving formats of the Research Assessment Exercise (now the Research Excellence Framework) have rewarded Departments and universities on the basis of their research output in a high powered way. This has been ferociously effective. As a whole, UK universities have vastly improved the quality and quantity of their research and now stand close to the very top of the international rankings.

One key insight is that while the RAE/REF itself is a collective Department-level incentive, this has trickled down to incentives for individual lecturers and professors. Universities keen to improve their research rating have created a “transfer market” for star researchers, and this has meant that recruitment effort, salary and respect have been focussed overwhelmingly on research ability. Young academics, wanting to get on, are aware of this and so spend their scarce time and energy on research.

This is not necessarily a bad thing – research is extremely important to a nation’s prosperity and cultural wealth. But it does mean that universities and individual academics have been incentivised to spend more time and resources on research than teaching. Does the Browne Review change any of this?

One of the less discussed points in the Browne Review is that new institutions can provide higher education (HE). Obviously, a new start-up university may find it hard to develop credibility for its degrees, but David Willetts, the Minister for universities, has floated the idea that they could teach towards the degree exams of established universities. This has worked in the past, and would give instant credibility to the degrees.

This opens up a range of possibilities. It seems unlikely that any single new institution would attempt to offer degrees across the whole range of disciplines. Instead we might see institutions offering, say, just a BSc in Computer Science, or just a BA in Spanish. This is reminiscent of the Independent Treatment Centres that transformed outcomes in health care; centres just doing cataracts or just hips. Obviously this does not provide the breadth of three years spent in a traditional university – chatting to people outside your subject, quizzing the great researchers in your field – but it would allow students to choose between these options and put a price on those factors.

Would this affect traditional universities, and alter the incentive structure for lecturers there? After all, this is where the bulk of students will be taught for the immediate future. It might. A new source of demand for talented degree teachers would raise their outside option and might force the traditional universities to pay more. The outcome depends in part on the co-production of teaching and research. Are good teachers good researchers, and vice versa, or not? What evidence there is suggests no strong correlation either positive or negative. In which case, there will definitely be an overlap in demand between traditional universities and new providers.

Of course, traditional universities will respond and make clear that their products are different, are distinctive. But they are likely to be more expensive too, and this gives students choices. There is likely to be a lot of innovation in institutional form and contracts following this path. How this will all pan out is unclear – the market for higher education is a complex one.

But it also creates a new market for talented degree-level teachers, and this may spill over into the pay and status of good teachers in universities. This in turn will encourage a re-balancing of lecturers’ effort towards teaching at the margin, and may have a greater impact on the quality of teaching in universities than any increased resources that may flow into the sector.