Archive

How should long-term unemployment be tackled?

Author: Paul Gregg

How should long-term unemployment be tackled?

Earlier in the week, George Osbourne announced new government plans for the very long term unemployed. The government flagship welfare to work programme, the Work Programme, lasts for two years and so there has been a question about what happens to those not finding work through it. Currently only 20% of those starting the Work Programme find sustained employment, although many more cycle in and out of employment.

Very long-term unemployment (2+ years) is strongly cyclical, almost disappearing from 1998 to 2009, but has returned with the protracted period of poor economic performance. This cyclicality is a strong indicator that it is not driven by a large group of workshy claimants. Rather the state of the economy leaves a few who unable to get work quickly face ever increasing employer resistance to higher them. Faced with ample choice of newly unemployed these people look like unnecessary risks with outdated skills.

Very long-term unemployment is thus not a new phenomenon and a large range of policies have been tried before and hence we have a very good idea of what does and does not work. The proposals had three elements. The first which got the headlines was that claimants would be made to ‘Work for the Dole’. The effects of requiring people to go into work placements depends a lot on the quality of the work experience offered. Such schemes have three main effects: first, some people leave benefits ahead of the required employment. This is called the deterrent effect and is stronger the more unpleasant and low paid (eg work for the dole) the placement is. Then, whilst on the placement, job search and job entry tend to dip as the person’s time is absorbed by working rather than applying for jobs. Finally, the gaining of work experience raises job search success on completion of the placement. This is stronger for high-quality job placement in terms of the experience gained and being with a regular employer who can give a good reference if the person has worked well.

The net effect of many such programmes, including work for the dole, has often been little or even negative. Australia and New Zealand have all tried and abandoned Work for the Dole policies because they were so ineffectual in getting people into work. The best effects from work experience programmes come where job search is actively required and supported when on a work placement, where the placement is with a regular employer rather than a “make work” scheme and where the placement provider is incentivised to care about the employment outcomes of the unemployed person after the work placement ends. The Future Jobs Fund under the previous labour government, which placed young people into high quality placements and paid a wage, was clearly a success in terms of improving job entry although the government cut it.

This element of the government’s plans has little chance of making a positive difference. However, the other elements maybe more positive. Some, the mix across elements is not clear yet, of the very long-term unemployed will be required to do daily signing. This probably means that the claimant will have to attend a Job Centre Plus office every day and look for and apply for jobs on the suite of computers. This is very similar to the Work Programme but more intense and perhaps with less support for CV writing and presentation etc. This may enhance the frequency of job applications but perhaps not the quality and may prove no more successful than the Work Programme. The third element is to attend a new as yet unspecified programme. As there are few details as yet it is hard to comment on this part.

The overall impression is that the announcement is of a rehashed version of previous rather unsuccessful programmes founded on a belief that the long-term unemployed are workshy rather unfortunates needing intensive help to overcome employer resistance and return to work.

The UK Employment miracle and productivity catastrophe

Author: Paul Gregg

The UK Employment miracle and productivity catastrophe

There has been a great deal of discussion concerning Britain’s recent employment and productivity record which has regularly been asserted as baffling economists and the bank of England. In essence the conundrum is that employment has recovered to pre-recession peaks whilst in terms of output the recovery has been very limited and stands well below (4%) that peak. This extended fall in productivity (making less with the same workforce) stands in massive contrast with previous recessions and recoveries where productivity growth was strong in the recovery. The figure below drawn from the recent ONS (2012), The Productivity Conundrum, Explanations and Preliminary Analysis by Peter Patterson, shows the productivity gap compared with the 1980s and 90s recessions stands in excess of 15% – a massive underperformance in terms of productive potential. A similar underperformance is apparent if we compare where we are compared to pre-recession trends. In the past, here and abroad, a loss of output compared to trend as a result of a recession, is subsequently unwound through a catch-up period of above trend growth this hasn’t happened, and a similar story is true of other countries. Whether any of this lost potential is recovered in the near future thus rests on why we have underperformed recently. This is actually easier to explain than the media description of baffled economists implies.

Productivity Levels compared to Pre-recession peak in four UK recessions.

Data

The first question concerns data reliability. Could some of the paradox be down to measurement problems? Certainly tomorrows GDP numbers for Q3 of 2012 will show a return to growth after last quarter’s numbers which were suppressed by the Queens Jubilee bank holiday and will suggest the economy is just growing over the past 6 months but this won’t make a dent on the sustained underperformance described above.

As mentioned previously employment has recovered to the pre-recession peak but unemployment remains very high. This apparent paradox is easily explained. Right through the recession employment among the over 65s has grown quite rapidly. Older workers are not retiring as they used to do, pushed by changes to retirement rules which encourage longer working and penalise early retirement and for women the rising state retirement age. So compared to the early 2008 employment of the over 65s stands 250,000 higher and a similar magnitude of extra employment has occurred among women between 60 and 65. Nearly all of this extra employment among older workers is either part-time or self-employed and often both. When we add in a growing population the proportion of the working population in work stands at 71.3% still well below the pre-recession peak of 73%, a shortfall of nearly ½ million jobs. Further there has been a sharp trend of more people wanting to work, especially among those aged between 50 and 60. This has been going on for a decade now but until recently this was offset by more people studying when young – so the share of the population wanting to work was constant at just under 77%. Over the last two years this increase in students has stopped. Perhaps because of a surge in the immediate recession period or a response to policy changes but either way it is adding another quarter of a million to the workforce so that whilst employment has reached previous peaks, the need for work stands considerably higher with a deficit of a million or so jobs. The move to more and more people wanting work, especially among older workers, and so we need to add at least 250,000 jobs a year to stand still and the employment recovery is thus not as good as it first appears. Allied to this is the rise in the numbers working part-time who want to work full-time, which is called under employment. The numbers who are unemployed stands at 1.4 million is shortfall which when combined with 2.5 million underemployed suggests huge unmet need for work. However, the fact that most of the jobs created since 2009 are part-time, fewer hours worked only accounts for about 1% of the productivity decline since 2008 (ONS, op cit).

It has been suggested that there may have been an under recording of employment before the recession, with a large number of migrants not being captured and that these marginal workers have since lost work and left the country again unrecorded. There are a number of major problems with this argument. First, our data on employment comes from two very different sources, one based on households and the other firms. Neither of them questions the legitimacy of an immigrant’s status and so there’s no incentive to hide migrants; therefore in terms of residence these migrants might be hard to find and perhaps be reluctant to reply to a survey, employers have no incentive to hide these workers and both surveys tell the same story about employment. If the firms using this labour are not tracked by the ONS then they will not be present in the output data nor the employment data and hence can’t explain the paradox. In addition it requires a huge number of missing migrants to explain the gap, at least 8% of the workforce and that all these workers lost their jobs with the recession. If only one in five lost their jobs, compared to 1 in 20 in the rest of the population, the numbers would need to be equivalent to 40% of the workforce. This is just implausible.

So the employment story is clear there has been an employment recovery, verified in a number of sources, but this recovery has not met the increased demand for work in the population, leaving 3.9 million unemployed or underemployed. The output side of the story also appears validated by tax receipt data. The ONS report shows how tax receipts VAT, PAYE and in total track the picture of nominal GDP well. That is the total size of the economy measured at current prices and serves to track government receipts well. However when we talk about output we take out the effects of inflation, so there could be a concern the effects of inflation have been overstated and there is more real output out there than estimated and low price increases. This argument tends to be supported by other inflation measures we have, the Consumer Price Index and Retail Price Index (which also includes housing costs) all show that inflation has been strong through this recession. So measurement can only explain a very small part of the story of economic underperformance with a good employment performance.

This provides a serious paradox, so where can the explanations lie? The first argument is one I would have made two years ago, that firms were hoarding labour in the face of recession. In the first phase of a downturn, firms who are profitable will hold valuable labour, with its skills and experience in the expectation that it will be needed again in a year or two as demand returns. Only if a firm is in acute financial distress does it shed skilled labour, when the firm’s very survival is at stake. This was thus eminently plausible in the early part of the recession. But firms hoarding labour would not recruit new staff to replace those that leave through natural wastage, move to a new job or retire etc. Hence such labour hoarding should start to unwind even if there is no economic recovery. Rather we have seen the reverse of increased employment without growth. Even though surveys show some firms hoarding labour this should be a diminishing issue rather than a growing one. As such this cannot be it can’t be the major explanation of current trends.

A variant on this is, if you like, is firm hoarding or as NIESR has described it ‘Zombie firms’. The argument is that banks are not lending to new or expanding firms as they seek to rebalance their own finances. It should also be noted that equally they are not forcing poorly functioning firms into bankruptcy and thus increasing bad debts held by the bank, and as such they are being allowed to persist despite the implied capital misallocation. The argument therefore runs that firms are expanding without capital through increasing employment rather than investment, whilst poorly performing firms are employing workers but are experiencing low productivity because of low order numbers. This is attractive and it is certainly the case that investment is low but there is no evidence to date that this low profitability Zombie sector exists. Certainly overall firm profitability is high outside manufacturing, which continues to struggle. Profitability in the dominant service sector is only slightly lower than in pre-recession period and recovered two thirds of the lost profitability during the recession, which in itself was quite muted compared to previous ones. As such the evidence of zombie firms is not obvious and requires an investigation of company level data for further insight, but at first take it does not feel like it is a major factor.

Net Financial Balance of Private non-financial Companies (from Peter Patterson The Productivity Conundrum, Explanations and Preliminary Analysis, ONS, 2012 )

The evidence of low investment is strong however; firms normally borrow money and invest in productivity enhancing technology. Currently firms are saving money rather than spending and are net lenders not borrowers. This is now evident on a very large scale and well that seen in the last recession at a massive 4% of GDP. The scale of this seems to point to healthy profitability being saved rather than invested as opposed to Banks not lending to growing firms and trying to reduce the net debt position of struggling firms. So why would healthy firms choose not to invest?

The obvious answer is that in the current environment it is easier, cheaper and less risky to hire to meet demand rather than invest. Real wages have fallen steadily since late 2008 and saw a large squeeze in the high inflation burst in 2011. Overall wages have fallen by around 8% since early 2008 in real terms (measured using Retail Price Index), this squeeze on wages is more than enough to explain the fall in productivity since 2008. Using a standard elasticity of demand for labour of around -0.5 then an 8% fall in real wages would raise employment by about 4%. In a period of uncertainty about future demand building cash reserves rather than investing for the long term is safer. Employing extra labour is easy to reverse if demand for product turns out worse than expected. At complete variance with the rhetoric of parts of government and their advisors and evident from firm behaviour hiring workers is easy and low risk. By contrast investments are largely irreversible and therefore inherently more risky. Hence as labour is increasingly cheap and low risk firms are choosing this route rather than replacing ageing infrastructure and machinery.

The apparent divergence between productivity since 2008 compared to previous recessions is huge but can be usefully broken into two parts. The first is that employment has recovered to pre-recession levels despite output still being 4% below the peak. This is partly explained by employment composition moving toward part-time work but mainly because labour has become increasingly cheap and low risk and hence firms are substituting labour for capital. This is occurring because real wages have seen such a large cut over the last four years. Research I’ve undertaken with Steve Machin for the Resolution Foundation shows that this in turn is a combination of a slowdown in real wage growth that occurred well before the current recession In addition there is clear evidence that wages have become more sensitive to unemployment such that the near doubling of unemployment from 4.6 to 8.3% we’ve seen since 2008 results in real earnings being £750 lower now than would have been the case from a similar unemployment rise in the 1990s recession. These changes have their origins in the decline of trade unions, a reduction in the imbalance of unemployment across skill groups and regions and welfare reforms which have meant that the completion for jobs is more intense. The larger part of the shortfall in productivity compared to past trends and recoveries however, stems from low demand in the economy and the corresponding absence on investment to meet that demand.

The implications are threefold. First, employment will rise and unemployment will fall well before there is a recovery in wages and productivity. However, as unemployment falls real wages will start to grow again as the heavy downward pressure on wages in the current labour market eases. This is the pattern already and it will continue until unemployment is firmly on a sustained downward trajectory. When output starts to recover and real wages stop falling firms will mostly likely start to invest their large cash surpluses currently held. This of course, need not all be in this country and the location of this investment will impart depend on the quality of the available workforce and the large scale geographical focus of world growth, with European economic recovery, including the UK, being more important for us. When this dam holding back investment is broken a period of strong growth should follow, as investment and rising wages fuel growth and hence perhaps 2/3 of the lost productivity will be recouped. However in my view at least 1/3 of the 15-18% shortfall in productive potential is lost. The longer the period of high unemployment, falling real wages and low investment continue the greater the damage that will be done.

The policy prescription that follows is reasonably obvious. First, incentives for firms to invest now rather than in the future need to be enhanced. This need not cost a low to the exchequer just rather a change in timing. Second we need to boost other investment in housing, lending to small firms and new low carbon technologies. This could happen through the government borrowing more, the treasury acting as a guarantor for borrowing by housing associations to build more low rent housing (so resources can be drawn from pension funds and the like) or through quantitative easing being invested through a national investment bank rather than used to try and manipulate bank finances. The government is feeling its way slowly to the second option whilst hoping that it doesn’t need to go further. Meanwhile Rome burns.

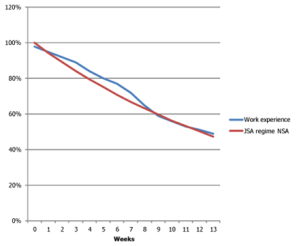

Work experience

Work experience programmes to help get the unemployed back into regular jobs have a long and somewhat chequered past. They have two distinct and offsetting effects; first the work experience itself is valuable. It gives an opportunity for the unemployed person to signal good work habits, including turning up on time and self-motivation when at work. These are the basics that employers want, after skills and experience. A decent reference from another employer is a big plus when looking for work. Obviously this is more important for those who have been out of work for a long time, or for young people with little previous work experience. However, whilst a person is on a work experience programme job search activity diminishes. The participant is working which simply reduces time available, but it is as important that they focus on trying to impress the firm they are based in, in the hope of being kept on. This is called ‘Lock In’ in the jargon of such schemes. These two effects are clearly visible in the Figure below (taken from the CESI website http://www.cesi.org.uk/blog/2012/mar/work-experience-more-be-done). It shows the proportion of participants in the government’s current Work Experience programme who are still claiming benefits week by week once they start participating (the blue line), compared with those who do not participate (the red line). For the duration of the placement, the first eight weeks, the proportion still claiming is higher by about 5% and then they rapidly catch up. So whilst they are on the experience programme job entry falls but once it has ended the positive effects start to kick in.

In this comparison the net effect is zero. This doesn’t definitively suggest that the programme has no beneficial effects for those participating, as we can’t be certain that those joining are not those who would have found securing work harder. They could of course be the more keen participants, or those in places where more firms offer placements, we simply can’t tell. However, this story of ambiguous effects with little overall impact on people’s chances of securing jobs has been the norm of Work Experience programmes since the 1970s. Unless, the design actively tries to minimise the adverse effects on job search and maximise the positive part of the work experience.

The first key ingredient is to maintain and support job search throughout the placement. That means requiring and monitoring the participant’s job search activity, as is the case when people are on unemployment benefits. Furthermore, the support services that welfare to work providers deliver to the long-term unemployed, such as CV writing and job interview techniques need to be in place to make the most of the experience. Finally, the agents delivering the placement, both the provider and the firm, need to care about the person getting a job after the placement. The easiest way to guarantee this is a bonus payment if the person is kept on by the firm or another job is found shortly after completing the placement. Small firms especially have a lot of contacts they can use to help place someone. Hence it is generally most valuable for private or third sector firms to house the participant rather than in the public sector.

Labour’s New Deal programme launched a decade ago now, had some of these ingredients but in sequence rather than all at the same time. There was a Gateway phase before the placement for support and intense job search, and again at the end in a Follow-through phase, but not when actually on the experience part. However, it didn’t have any outcome related payment for firms or charities providing the experience. By comparing those aged 24 who joined the scheme at 6 months, with those aged 25 who had to wait until 1 year, we got a sense of its effectiveness. A study by John van Reenen (LSE) showed clear job entry gains for participants, although it didn’t assess how long the gains lasted as the older group also joined the programme.

The current Work Experience programme for under 25s starts much earlier at just 3 months, which means there are more potential participants and many more will find work quickly without help. For this reason the government is keeping costs down to a minimum. The placements are not paid and no support services are provided, no job search monitoring is in place and there are no bonus payments for firms who take participants on. Hence it should be no surprise that the scheme appears to be making little or no difference.

Labour has just launched its ideas for a more intensive, 6 month paid programme starting after 12 months on unemployment benefits. These are a much smaller group with much greater need; people who go on to have very damaged working lives well in to their 40s unless they can get attached to long-term stable employment. With signs of intelligent design, the programme has all the key ingredients for making a difference, except outcome payments for the firms. Participants will have a support service provider whilst on the programme who is only paid on the basis of getting the person into work, the work experience is part-time to leave time for job search and as when receiving benefits normally, active job search is monitored and sanctions will apply if it is not undertaken. So the scheme has a decent chance of making a sufficient difference to cover its costs. But the other issue, apart from there being no bonus payment to firms getting participants into work, is that it is drawn very narrowly. By requiring a person to be on unemployment benefits for as long as a year means that many cycling between short term jobs and unemployment are missed. Those leaving school at age 16 or 17 who don’t get work are not entitled to benefits, and will still have to wait a year (until they are 19) before help kicks in. There is also no help for the 16 and 17 year old unemployed. So, it is a good first instalment but more will be needed to end long-term youth unemployment.

The cost of youth unemployment

Paul Gregg and Lindsey Macmillan

In hard times, young people face two hurdles to finding work. First, firms tend to hold onto their existing experienced staff but stop recruitment to reduce their workforce. This collapse in new vacancies hits young people hardest. Second, with more unemployment comes more choice of potential employees for firms who are hiring. Firms favour previous experience placing young people in a catch 22 situation of not being able to get the experience they need to get work because they can’t get the work in the first place. For the least educated or those who are unlucky enough to experience long periods out of work now, it is increasingly hard to get that break that opens the door to the labour market.

As the number of youths who are out of work continues to rise the exchequer is left counting the cost. Each 16-17 year old in receipt of benefits costs an average of £3,660 a year whilst each unemployed 18-24 year old who claims costs an average of £5,600 a year. Even though many young people don’t claim benefits, just 19% of 16-17 year olds not in education or employment and 65% of 18-24 year olds with the sheer number of young people out of work, plus the additional tax and NI revenue lost through the lack of earnings, the numbers are non-negligible. In total, the current cost of youth unemployment to the exchequer is £5.3 billion per year. The productivity loss to the economy, often calculated as the wage foregone to measure the output lost, is £10.7 billion. The large numbers not claiming benefits and the low value of benefits relative to potential earnings makes an important point that work incentives are very strong for this group.

On top of these current costs, there are also long-term scars to youth unemployment in the form of future unemployment spells and lower wages. We can see from previous generations’ experiences of youth unemployment that the longer the period spent out of work in youth, the more time spent out of work later in life and the lower potential wages were when in work. This evidence on the future costs of youth unemployment comes from two UK birth cohorts that track all babies born in a window for the rest of their lives. By chance, the participants in the first cohort were aged 21 when the 1980s recession hit and in the second cohort, the participants were aged 20 when the 1990s recession hit. Around one in five young people in the first cohort spent over 6 months out of work before age 23, and it was similar in the second. Furthermore these people spent about 20% of their time unemployed 5 years later and 15% even 12 years later.

For males in the second birth cohort, an extra month out of work before age 25 raised the proportion of time out of work between age 26 and 30 by three quarter of a per cent; an extra year out of work in youth led to 10 months more unemployment later in life. It is a very similar story for wages with an extra month unemployed when young associated with 1% lower wages in their early thirties. It’s possible that these legacies may not reflect just the pure effect of youth unemployment but also that those experiencing more unemployment are less well educated and come from deprived backgrounds. The great advantage of the birth cohort studies is that so much is known about the young person’s childhood from their education to their attitudes and beliefs, their health, their wider circumstances and almost as much is known about their parents. The evidence suggests that about half of the later lower wages and higher unemployment exposure stems from these background differences between people and about half is a result of the unemployment itself.

The cost to the individual’s future is therefore large. However, it doesn’t end there. There is also a future cost to the public purse in terms of future benefit claims and tax revenues lost from lower earnings as a result of this scarring. Estimates from the second birth cohort suggest that the average unemployed young man will cost the exchequer a further £2,900 in future costs with the average unemployed young woman costing £2,300 a year. Aggregating these up in the context of the current youth unemployment crisis leads to further future costs to the exchequer of £2.9 billion. The future productivity losses in terms of output lost are estimated to be £6.7 billion. If we add the exchequer costs together to give the combined future and current costs of youth unemployment (discounted to adjust future costs to be equivalent to today’s) the total cost to the exchequer is therefore £28 billion. These numbers suggest that doing nothing about youth unemployment is and will continue to cost us dear.

Unemployment and the Euro-zone Crisis

Chris Grayling, the Employment minister, firmly laid the blame for the rapid rise in unemployment in yesterday’s figures on the Euro-zone crisis. This argument is so obviously bogus, it is disappointing for a minister to be using this as a line of defence. However, the labour market figures are not as bleak as the headlines suggest. The effects of the Euro-zone crisis will hit us over the next six months, not the last, and the minister should have kept his powder dry as he’ll need this excuse in the coming months.

The argument presented is; the Labour Force Survey (LFS), which is the main data source on the labour market, showed a growth in employment until June, after which it appeared to go off a cliff with employment falling 190,000 in the three months leading up to September. The problems with this argument are threefold. First, the Euro-zone crisis broke in July and the performance of the UK economy since then has been the best in a year; a point made by the latest retail sales figures which show very healthy growth in September and October. So far rather than the Euro-zone crisis damaging growth we have been doing rather well. The danger lies in the future not the recent past. Second, employment and unemployment figures are driven by decisions made by firms, and it takes about three to four months for this to be seen in the data. For example, the latest data from September 2011 reflects the state of the economy in May-June rather than prior to the crisis. Finally, the LFS is only one of four data sources about the health of the labour market. Over the big sweep of boom and bust events, these track each other well, but on the specifics of timing there can be wobbles in any one of the series; looking at the set offers a better picture. In addition, the LFS have a survey of employment from employers, a survey of current vacancies and the count of all those claiming unemployment benefits. The last two offer the most up to date picture, but the LFS and employer survey are more comprehensive. All three indicators, other than the LFS, suggest that employment started to fall and unemployment started to rise in February or March this year. The claimant count bottomed out at 1.45 million in February and has risen every month since at a steady rate of 20,000 a month or so. Vacancies currently offered by employers almost reached 500,000 in January before slipping back to 460,000 since May; a level consistent with low levels of net job losses. The employer’s survey only runs to June at the moment but says that employment peaked at 26.7 million in March and fell by 100,000 by June.

The LFS clearly looks like it mistimed the move back to job shedding by three months; this happens quite often but rarely matters much. The broader data clearly shows two things. First, that the labour market downturn precedes the Euro-crisis by some months and is totally in line with the downturn in UK economic growth, which started in November last year. Second, that the employment shedding and unemployment rise has been pretty constant since March, rather than a recent collapse. Both of these stories are clearly at odds with the Euro story. But the rub is that the evidence suggests the latest sharp rise in unemployment in the LFS is a catch up from previously understating the rise. The labour market hasn’t, yet, gone off a cliff. Indeed the healthy growth and small rise in the claimant count may say things were improving a little as the Euro-crisis broke. So the overwhelming picture is that the current sharp rise in unemployment isn’t driven by the Euro-crisis but is also not as sharp as it first appears. The Euro-crisis excuse may well be needed, and be genuine, from March next year when the picture around January starts to emerge. But for the latest figures it is entirely bogus and also misses the deeper picture.

Disability benefit claims

Department for Work and Pensions figures released this week suggest that only 7% of applicants for the new disability benefit, Employment Support Allowance (ESA), during the two years since its inception, are found unfit for work. The implicit suggestion is that the previous regime was widely abused by ‘scroungers and malingerers’. Yet the total number of claims for disability related workless benefits is almost exactly the same, at 2.6 million, in the latest data (November 2010) as it was in 2008, when the new benefit started. Even among claims less than two years old and hence all assessed under the new regime there are 640,000 claimants, which is exactly the same as in 2008. So, how can the impression of a big crackdown on claims under the new test, and the absence of any decline in numbers claiming be reconciled?

The answer is three fold. Firstly, although only 7% of new applicants go on to be deemed unfit for work, another 17% are eligible for ESA, but deemed that with the correct support and improvements in health they may get back into work. ‘May’ being the important word here. I designed the structure of support for this group under the ‘Work Related Activity Group’ banner, which will be delivered under the new Work Programme. How successful it will be is yet to be demonstrated. So, 24% of new claims go on to be eligible for ESA, not 7%.

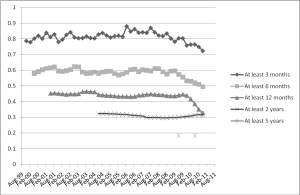

The second key point is that a large number of applicants never got onto Incapacity Benefits (IB), the forerunner of ESA, either. Some people simply got better before the assessment phase was completed and so never got tested, or were denied access through the test applied at the time. People start a claim for disability related benefits but begin in an assessment phase, during which they receive the same benefits as they would for unemployment. It is only after this is completed, at around 13 weeks, that the recipient receives the eligibility decision as to whether they move on to the full ESA benefit. A lot of people withdraw before the test occurs and always have; 36% of applicants in the new figures. A useful guide to this would be what proportion of claims under 13 weeks go onto the main benefit. However, as so many claims go to appeal, during which time people remain as though they are still in the assessment phase, a better picture emerges after 6 months. The figure below highlights the survival rates for claims before and after the new ESA regime was introduced in late 2008. It shows the proportion of claims under 13 weeks old, and hence in the assessment phase, which are still live a further 3 months, 6 months and so on after their commencement. After 3 months some 72% of applicant’s claims are still live and after 6 months this falls to 50%. Of key importance here is that this was around 80% and 60% respectively under IB pre-October 2008. Hence, ESA has reduced the numbers of applicants reaching at least 6 months duration by 10%, and this appears to persist through to the longest duration data we have. So the new regime is leading to around 10% fewer people, after the appeals process is completed, being passed as eligible for ESA. A story far removed from just 7% being found unfit for work.

The third reason this has not had any effect on the total number of claims under 2 years duration, and thus assessed under the new test, is that the total number of new claims has risen from around 130,000 per quarter in 2008 to around 160,000 now. This is almost certainly as a result of the recession but past experience suggests it will take quite a long time to abate fully. So, between 1 and 2 years duration we now have the first quarter of data that is fully under the new regime. After all the assessment and appeals have been completed we can derive that the number of claims has fallen to 206,000 from about 235,000 prior to the reform. This is around 12% lower, but this is currently offset by shorter duration claims. As time progresses and the impact of the recession diminishes the new ESA tests will make a clearer difference to the total number of claims. However, it will be a long time before this is very visible. What will be more important over the next 3 years will be the re-testing of existing IB claimants, as well as the removal of eligibility to ESA for those claiming for more than 1 year and who are not eligible for means tested benefits.

Figure 1 Proportion of Claims of 0-13 weeks duration that are still live after intervals specified

Employment and Growth Paradox

Two high profile commentators, Stephanie Flanders of BBC and Chris Giles of the FT have noted the paradox of a stagnant economy as measured by GDP growth co-existing with an apparently booming labour market. The GDP numbers suggest that over the 6 months to March the economy registered no economic growth, but the Labour Force Survey for the 3 months to March says we added 80,000 jobs and the employer-based survey a whopping 120,000 in the same period. This disconnect between growth and jobs was also apparent through the recession. The recession was the worst since the Great Depression but the numbers of jobs lost was very modest compared to that in the lighter recessions of the early 80s and 90s (see Figure). Just 2% of jobs were lost compared to 6% previously. This labour hoarding through the recession appeared to be related to high profitability of firms prior to the recession and a maintenance of consumer spending through radical cuts in interest and VAT rates. But it raised the prospect that firms would have the potential to raise output without new workers as productivity recovered to pre-recession levels. This didn’t happen so that once growth started in late 2009 employment responded very quickly – no jobless recovery here.

So the current apparent paradox could either be just a statistical anomaly that will be reversed soon or perhaps a sign of a deeper issue that Britain can create jobs easily but at the cost of slow or non-existent productivity increases, which will knock on to slow or non-existent real wage rises until unemployment is reduced substantially. The first point of view is supported by other labour market data. The claimant count has been rising since February and at an increasingly rapid rate and vacancy levels falling since December. The rise in the claimant count has come about through a decline in numbers leaving, as is normal when vacancies dry up, rather than more new claims. This rise therefore cannot be attributed to moving people from lone parent of sickness benefits on to JSA. So there might just be a rather longer lag between the growth soft patch, as Mervyn King calls it, starting and jobs growth halting, than we have seen of late. The alternative view that we are seeing UK productivity stuck in a morass, also has merit. High unemployment is suppressing wage growth, so that it is becoming cheaper, even against price rises UK producers are securing for their output. The recession was particularly centred on a collapse in company investment and the stasis in the banking system means UK firms are still struggling to raise capital for investment. The norm used to be that almost 2% growth was need to keep employment level, as productivity rose and growth of 2.5% before unemployment fell as below that job creation only matched population growth. With so much labour to absorb in terms of a growing population, in-migration and a remarkable increase in working among people beyond normal retirement age, it is astounding unemployment has fallen over the last 6 months at the rate it has. So whilst the labour market is in all probability softening now and employment is likely to stop growing, we seem to be generating jobs with just 1% annual growth rates, which is good news in terms of unemployment but it implies that poor growth is hitting productivity more than jobs, which in turn means the prospects for a return to rising living standards in the UK may be a long way off.

The Work Programme

The Work Programme is the Government’s replacement for Labour’s Flexible New Deal which in turn was preceded by various New Deal programmes. The new programme will have three new features which are distinctive and potentially positive. First, it will operate a single programme for multiple client groups but with three different major fee rates. Providers running the programme will receive fees for helping clients into sustained work with the regular adult unemployed forming the bulk of the cheapest group. The young unemployed are the main group in the middle tier and those with significant disabilities forming the most expensive tier. This step has been planned for some time with the move to Employment Support Allowance replacing Incapacity Benefits and the development of a welfare to work strategy for the disabled. However, this integration is the first time that the UK has operated a clear unified programme which offers real hope of reducing long-term marginalisation of this group from the labour market. The second major advance is that the full payment to providers for getting people into work will not be paid until a person has been in work for a year rather than 6 months, and two years for the sick and disabled. This will encourage providers to think more about job matching and indeed job quality as better paid permanent jobs have a far greater likelihood of paying out. Third, the programme is fully “black box”: there is no prescribed provision or minimum service agreement. This will facilitate use of new group/team based working rather than one-to-one fortnightly meets which dominated the minimum service agreements and are probably poor value for time and resources. Team or group based working has a good history of helping through peer support as well as being low cost.

What is missing, in my view, is discussion of a number of issues which have not been dealt with previously, and a couple which are particular to the new programme. For young people, even though youth unemployment is high, very few NEETs will be on the Work Programme. Only around half of 18-24 year olds not in work or education are signing on for Job Seekers Allowance and only a minority of these have a single spell of claiming that is sufficiently long to join the Programme.

Hence most will miss treatment because they get spells of short term work or training or don’t sign on. In terms of benefits spending this may appear acceptable, but we know that these individuals who fail to connect to sustained work go on to have very poor earnings and frequent spells of unemployment when older. A window based on the person’s recent history of worklessness is necessary for entry to the programme, rather than single spell duration and those not on JSA need to be identified and tracked to facilitate re-engagement.

A further long standing problem is that DWP contracts on a fixed price for all those in a group. The risk is that the provider will focus on the easiest to help and not invest in the hardest. This is sometimes called parking; parking is likely to occur within the three group bands, although there are small extra payments for some groups within bands but is probably most problematic among the disabled where the huge variation in conditions and costs associated with getting them back to work may mean many are written off as too costly to help. The fees on offer are tight for providers and the poor labour market conditions will mean providers will struggle to match cost. In many cases winning the current contracts may well prove to be loss leaders until the next round of contracts. This means DWP may be getting very good value right now but there has to be a risk that some providers may withdraw or need contract top ups to keep going, as happened in Holland when this structure was introduced in the 1990s.

Statistical myopia, measures of unemployment and economic reporting

Today the ONS published a statistical bulletin of labour market statistics, which was widely reported as evidence of an increase in unemployment. However, the executive summaries provided by the ONS did not include sufficient information about the precision of the statistics. This led newspapers to report ‘changes’ in important features of the economy, such as the unemployment rate, that may in fact be due to chance.

Labour market statistics, provided by the ONS, are estimates, not exact measures. The statistics are calculated from surveys of thousands of people. This means that the statistics are subject to sampling variation. Therefore, if the ONS were to repeat their survey and calculate all their statistics on a different group of people we would not expect them to be the same. The ONS provide estimates of the size of this variation in additional tables: they estimate the range in which their statistics would be expected in 95% of samples. However, these ranges are not reported in the executive summaries, or in the much of the discussion of what the statistics show. The findings of the ONS bulletins are faithfully reported to the public by newspapers, but unfortunately without a measure of sampling variability, it is not possible to tell if the level of unemployment has changed, or if the reported change is consistent with chance.

The summary of latest labour market statistical bulletin reports the following statistics, to which I have added confidence intervals using the measures of sampling variation provided by ONS later in the document:

- The employment rate for those aged from 16 to 64 for the three months to November 2010 was 70.4 (70.0, 70.8) per cent, down 0.3 (0.0, 0.6) on the quarter. The number of people in employment aged 16 and over fell by 69,000 (-62,000, 200,000) on the quarter to reach 29.09 (27.53, 30.64) million.

- The unemployment rate for the three months to November 2010 was 7.9 (7.7, 8.1) per cent, up 0.2 (-0.1, 0.5) on the quarter. The total number of unemployed people increased by 49,000 (-37,000, 135,000) over the quarter to reach 2.50 (2.42, 2.58) million.

- There were 157,000 (137,000, 177,000) redundancies in the three months to November 2010, up 14,000 (-14,000, 42000) on the quarter.

- The inactivity rate for those aged from 16 to 64 for the three months to November 2010 was 23.4 (23.1, 23.7) per cent, up 0.2 (-0.1, 0.5) on the quarter. The number of economically inactive people aged from 16 to 64 increased by 89,000 (-26,000, 204,000) over the quarter to reach 9.37 (9.23, 9.50) million.

There are 7 estimates of change in levels. All seven of these changes are consistent with what might be expected from sampling variation, so the statistical bulletin provides no strong evidence of a quarter on quarter change in any of these statistics. The statistical bulletin contains further statistics that report the change in employment in sub-groups of population, by age or by region. Each of these sub-populations is smaller, and hence less precisely measured. Therefore estimated changes in unemployment in sub-populations, such as youth unemployment, are more likely to be due to sampling variation. However, we cannot know, as the sampling variation of these sub-populations are not provided by the ONS, so it is not possible to tell if these differences are important, or if they are just due to chance.

Understandably, given the executive summaries of the statistical releases, newspapers report that unemployment is rising, when the data do not support this. This leads newspapers to miss the bigger story: unemployment is still very high after the recession, and there is little evidence of falls in employment. The ONS could help by stating confidence intervals in their statistical bulletins to enable journalists to easily interpret whether the information in a report is consistent with chance, or if there is evidence of a genuine change. We know long term measures of unemployment, for example annual measures, with much more precision, because we have larger samples, so if measures of precision were to be more widely reported then debates over the economy might be slightly less myopic.

Growing Employment among Over 65s makes reducing unemployment more challenging

Economic growth this year, so far, has been exceedingly rapid at 3.2% on an annualised basis and employment has responded too, up by an impressive 286,000 since the same time last year. Yet unemployment has been broadly static, falling by just 17,000. The explanation behind this apparent paradox is going to make preventing unemployment from rising over the next few years very difficult.

The first factor is that the British population is increasing. This is coming more from natural growth than migration as the numbers of youngsters entering the working age population at the moment is strong. The increase in the working age population at just under 200,000 over the last year means that about 140,000 jobs are required to hold the employment rate at 70%.

This challenge is being added to by the way older workers are not retiring in the way they used to. Some 850,000 over 65’s now work, up nearly 100,000 over the last year and some 260,000 since the recession began. Furthermore, women aged between 60 and 65, that is above the normal retirement age now but where the retirement age is rising to over the next decade, have seen a further 80,000 increase over the last year. Hence, to cope with older workers delaying retirement means a further 180,000 jobs need to be created to hold working age employment stable; this means a total of 320,000 jobs a year. There is a slight offset from more young people staying in full-time education but job creation needs to be extremely rapid just to hold unemployment steady.

Given a likelihood of slower growth next year with tax rises and spending cuts then a rise in unemployment starts to look inevitable. With unfilled vacancies falling steadily for the last five months, and long-term unemployment rising rapidly now, up nearly 200,000 in the last year, the prospects look bleak.